On December 14, I gave a reading of the following piece at Cora Dance’s “Stone Soup” festival. It’s a revised version of some posts from the cross-country roadtrip I blogged in 2006; some of this may be familiar if you were following me back then.

In the summer of 2006, I set out on a road trip from Brooklyn to the Pacific Coast in Northern California. The trip actually began about a year earlier, during one of my darker moods, when Pink asked me, What would you do with your life if you knew you had six months to live?

I’d get a car and drive around and see the country.

What if you had a year to live?

Do the same thing, but stop in California and learn to surf.

The dark mood had probably been brought on by my job, which I hated, working at the Death Star. The idea of the road trip took up residency in my brain. I bounced it off some people. One of them was a playwright who had long earlier decided to live life on his own terms. He told me, When you have the chance to do one of these road trips, you have to take it. You don’t know when the next chance will come along.

So I took a buyout offer from the Death Star. I used some of the money to buy an orange Honda Element that I called Rocinante, after Don Quijote’s horse.

I found a couple of months when I could leave my other commitments to fend for themselves, threw my bike and some camping gear in the back, and pointed Rocinante west.

I set down some rules for myself:

No four-lane highways.

No chain restaurants.

Plan as little as possible.

Be wholly undiscriminating in deciding what might be worth stopping for.

To be clear: Not everything worth stopping for is worth staying for. For example, the One and Only Presidential Museum in Ohio, which purported to include all the presidents before George Washington.

I met the proprietor Nick, an unkempt, white-haired personality slumping in a stool at the bar adjacent to the museum. He explained the theory of the museum to me at length.

To be extremely - excessively - fair, Nick had a point - prior to Washington and our current Constitution, the United States operated under the Articles of Confederation. You probably spent ten minutes on this in history class once. And your history teacher probably didn’t bother explaining that the Congress elected a president, who was not in any way a president in the way we currently think of the job, and there were a bunch of these guys who each served a year or so, and …

As I said, Nick had a point, but it wasn’t an especially interesting point. Nevertheless, despite my best efforts to extricate myself, he held me hostage for roughly two hours expounding on life, the universe and everything. Two hours spent in that dark bar, desperately hoping to see the sun again. These are the risks you run when you are observing rules three and four.

Nevertheless, whenever a choice might arise – should I stop to see the second-largest concrete statue in the world, or press on? – a voice would say, When you gonna be back here again? And so I would stop.

Early on in my roadtrip I met up with my family at the shore of Lake Michigan where they had rented a cottage. I spend a week with them, and then they return home to Ohio, and I find myself alone and plotting a route, pulling out the Rand McNally road atlas I’m carrying with me and looking at where the narrow lines might take me. I kill another day or two at the beach, biking around and stopping in Grand Haven, Michigan, where I find glorious surf.

The red flags are flying at the beach to indicate no swimming, but the water is full of families and couples and kids laughing at their own puniness. Amid them, a hardy band of surfers is leaping off the pier, trying to avoid being bashed back against the concrete.

Mostly the surfers are getting kicked around by waves coming in from all directions at once. One of them, younger than the rest, is sitting on a rock with blood running off his foot. I ask one of the others, who is looking at the kid as if he has done his own time, looking at his own blood, on that very rock, if it’s always like this here.

"We usually like it a little cleaner," he says. But mostly he seems thrilled.

I stay a while, wade cautiously into the surf, take a mess of pictures, talk to a few more folks. I think about getting to California where my friend Pete has promised me a surfing lesson or two, and whether this trip will work out the way I imagine. So with that in mind I return to Rocinante, the pull of what may lie ahead proving stronger than the feeling that nothing could be better than this.

I’m off to Louisville where I’m going to hang with a friend for a couple days. The drive from southwestern Michigan to Louisville takes me through eastern Indiana, through towns called Goshen and Warsaw and Wabash.

The country here is wide and flat. If you hold a ruler up to the horizon, you can detect the curvature of the earth. In some little town I stop at a drive-in root beer stand where three people sitting under the overhang seem puzzled to see an orange Element with New York plates driving up. I’m stopping for the novelty of a root-beer stand, but it turns out that almost every little town in that part of the world has one. At one intersection I find competing drive-ins.

Rocinante and I plod along through the heat of an Indiana July to Marion, where I make the turn to Gas City.

Even allowing for Rule #1 (no four-lane highways), I might have found more direct routes to Louisville, but I planned a stop in Gas City because it was the home of the James Dean Gallery.

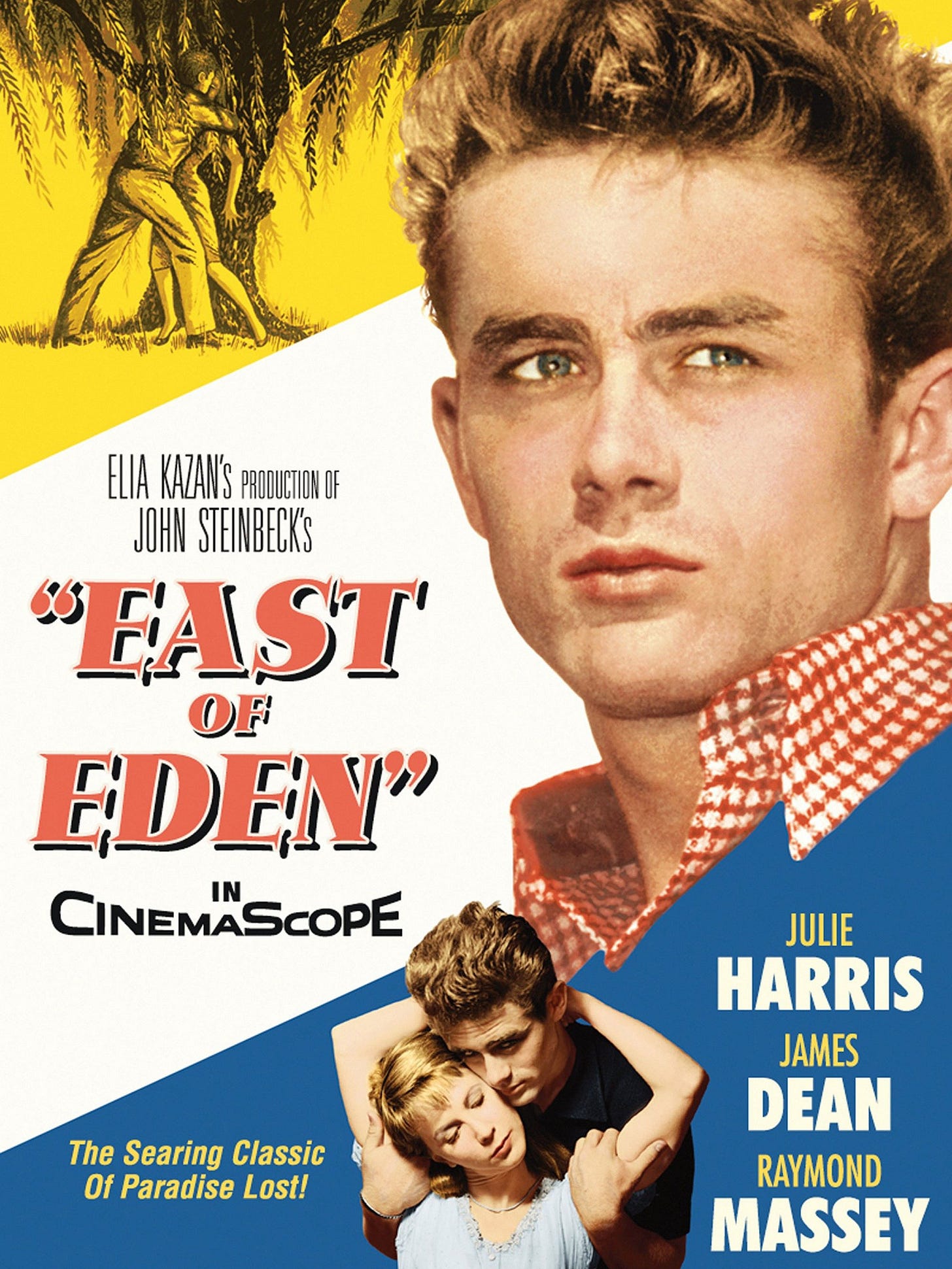

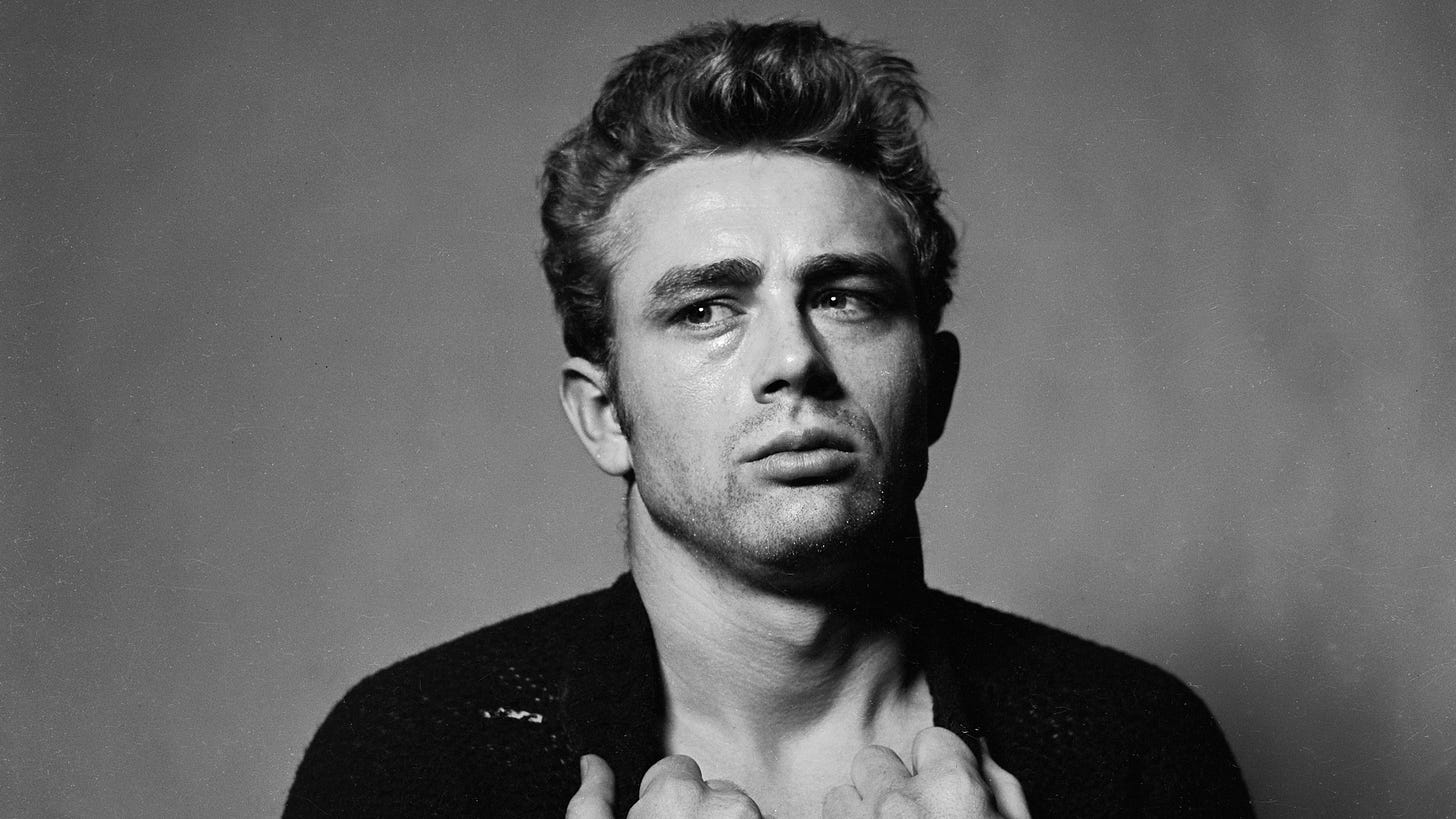

Seventy years ago, James Dean was a meteor streaking across the Hollywood sky. A bad boy with an irresistible, I-didn’t-mean-it smile and a vulnerability rarely seen in the era of John Wayne. He burst onto the scene in East of Eden, broke every teenage heart in America as a Rebel Without A Cause, and then tried to shake off that image in Giant.

And then …

Some months before my road trip, my friend Rosemarie told me about a report on NPR that the James Dean Gallery had closed and would be auctioning off its collections. Like me, Rosemarie has a keen appreciation for the oddities of roadside America. Places like Pedro’s South of the Border or the World’s Largest Ball of Twine or Carhenge - or the One and Only Presidential Museum. Places of a particular vintage, when people traveled by car and little towns lured visitors with one-of-a-kind sights that were always tacky and have since become kitschy. Rosemarie and I shared our regret that we had missed this example. She did told me that the report indicated that there were various other sites in the area worth visiting, though. So at Marion, I make the turn.

As I’m driving, I have in my head this utterly idealized vision of what Gas City will be like - like there will be some portal I will drive through, and suddenly it will be 1955 again - drugstores with soda fountains and Cadillacs with tail fins. But at Marion instead I find the usual, endless string of Wal-Marts and Applebee'ses. It occurs to me I might be in for major disappointment. I turn east on US 35, make my way around a detour at the railroad tracks and realize …

I realize that I have no idea what I’m looking for. I have relied greatly on good faith and serendipity thus far on this trip, and all in all I think that I have made the right choice in so doing. But on this July afternoon I’m considering that maybe the slightest amount of research on this particular point of interest might have been a good idea. It’s hot as hell, it’s 4:15 in the afternoon, anything worth seeing will be closing soon, and I don’t have a clue. And there’s nothing in Gas City to indicate where I ought to be headed. It may not strictly be 1955 in Gas City, but it looks like commerce just about stopped then.

Fortunately, Andrew Carnegie gave the good people of Gas City a public library, which is handsome and well-maintained and located right on Main Street. And the very helpful librarian pulls out the phone book and copies a map out of it and draws me a route around the detour and out the Fairmount Road toward the farm where Jim Dean grew up.

Which is not, it turns out, in Gas City.

It strikes me that I am quite probably the only person in the world who has ever traveled to the middle of Indiana specifically to see all the important, formative places in the early life of James Dean, and yet did not know that these sites are actually located in Fairmount.

You see, the James Dean Gallery had relocated to just outside Gas City, or more specifically, adjacent to Interstate 65, in order to attract more visitors. It apparently failed to do so, which led to its closure, which led to an NPR report, which led to Rosemarie calling me, which in turn, ironically enough, led me to be here.

So I thank the librarian and hop back into Rocinante’s saddle, and follow the Xeroxed map down Fairmount Avenue. And suddenly - I am not disappointed anymore. Half a mile outside of Gas City I have arrived, if not in 1955, then at a place that appears to live life much the same way. I pass beautiful farms and a graveyard that, if I were the sort of James Dean fan who knows enough to go to Fairmount, I would recognize as his resting place.

But I drive past it, on into Fairmount, where I immediately see a giant Victorian pile on the corner housing the “Rebel Rebel” gift shop.

It looks over the top, even for me - but the sign promises free maps, and at five after five I’m assuming the local historical museum will be closed, and Rebel Rebel might be the only straw to clutch at.

Inside I find David, the proprietor, who is just the sort of James Dean fan you might expect would open a gift shop in Fairmount, Indiana. More, actually: it turns out he was the founder of the James Dean Gallery, and it’s his collection that is headed to auction, following the museum's demise.

David is tremendously patient with me as I try, and mostly fail, to hide my James Dean ignorance. He introduces me to Lenny, with whom he runs the shop, and who hails from Coney Island and seems delighted beyond words to welcome a fellow Brooklynite to his world. David pulls out the Xeroxed map of Fairmount and highlights the way to the various sites: the memorial park, the high school where James Dean first performed, the shop where he bought his first motorbike, the gravesite, the Winslow farm where James Dean grew up. I ask if I'll be welcome there, and David says yes. If you happen to see Marcus outside, he says, he’ll probably stop to answer any questions I might have.

I have to ask who Marcus is.

Marcus Winslow, David patiently explains, is the local man who took James Dean in after his mother died when he was five. The Winslows raised him on their farm - not always lovingly, it seems.

These are pretty basic facts that the most superficial James Dean admirer ought to know.

And yet: maybe it’s because I have just driven into 1955. Maybe it’s because I have been so warmly greeted on arrival. Maybe because it’s getting to be magic hour, and maybe because I just want it to be. Or maybe it’s because I keep walking through the shop looking at pictures of the most beautiful man Hollywood has ever seen, and thinking about his death at the age of 24, and the way he looks at least ten years older in most of the pictures I’m looking at.

Which might have been acting, but was probably just unhappiness. And the way they hounded him, and I’m hounding him still, 50 years later.

Whatever the case. I'm sure I’m as honestly moved by all this as anyone else who has come here.

I drive to the various sites, the memorial park, and the high school.

Through a little downtown much prettier than Gas City’s, but no more thriving. Finally I head back up the road toward Gas City to see the gravesite.

And the Winslow farm.

The farm is all I had really come to see, and mostly because of a ballad written by Phil Ochs, “Jim Dean of Indiana.” It tells of his childhood, his father being absent, his mother’s death, the poor treatment he had at the Winslow farm. The hired man would beat him, the song says,

'Cause he would never do the chores

He was lost in dreamin'

And it talks about his escape to Hollywood. The song glosses over certain details, and maybe invents some others, like people running from the movie house to the Winslows’ to tell them they’d seen Jim Dean on the screen. And the song tells, in its elliptical way, of James Dean going off to the Central Valley of California to race on the road, and the crash that killed him.

I arrive at the driveway to the Winslow farm. It’s a lovely place, beautifully kept, running board fences painted white. The Hollywood ideal of a midwestern farm.

I don't see Marcus, and that's just as well, I suppose. After a few moments I turn the car back around and head back toward Fairmount. On my way through town I pass the motorcycle shop, and say to myself, When you gonna be back here again? And I pull in to take a picture.

I peer in the window for a moment, and then call my friend and fellow connoisseur of Americana, Rosemarie, to tell her where I am and to thank her for telling me about the radio report.

The crunch of tires on the gravel parking lot summons a woman from around the back of the shop.

There’s nobody there, she says. She introduces herself as Mildred Carter. It was her husband, Marvin, who sold James Dean his first motorcycle. "Jimmy" as she calls him.

We spend an hour or so talking in the shade of giant oaks, in the cool of the Indiana evening. Jimmy spent a lot of time at the shop, Mildred tells me; he didn't get along with the Winslows very well and preferred the Carters’ company. She tells me about the time Marvin asked Jimmy to drive over to Marion, five miles away, to pick up some parts. Jimmy didn't know how to get there; he'd never been to Marion in his life.

She tells me about the times Jimmy would call from New York to ask for $200, so he could eat. She tells me she’s 92 years old, and then shames me by bending over and pressing her palms flat on the ground. She tells me not so many folks come around any more - it's been fifty years, after all. She tells me about the trip they were planning to go see Jimmy in Los Angeles - which they never took.

He didn't have a very happy life, she tells me.

It’s getting late, it’s time to go. I’ve got to get to Louisville still. I return to Rocinante. The crunch of the gravel gives way to the pavement of the road, and Mildred sends me on my way with an air of gratitude, that I have taken time to talk with her about her friend Jimmy Dean.

What a wonderful experience. It really humanizes James Dean. My grandpa was a fan of old movies and we watched so many while I was child, I grew up with crushes on black-and-white Jimmy Stewart and James Dean and wanted to have Katherine Hepburn's spunk and Claudette Colbert's sass. I'm so glad you wrote about this and shared it.