This was supposed to be a post about The Poseidon Adventure, but my Gene Hackman film festival last weekend consisted of watching Hoosiers for the first time instead of returning yet again to the band of misfits trying to escape that upside-down ship. The Poseidon post is coming; I have much to say about why it might be my favorite movie. But before I can get to that, I have spend some time looking into why Hoosiers, although it will never be among my favorite films, got lodged in my brain.

(This will be spoiler-riddled, and I mean more than just telling you that I did not love Hoosiers - but for that, the box and everything else you may have heard about Hoosiers spoil all but the last ninety seconds of the story. Which I promise to keep quiet about.)

My sister, who was transplanted to Indiana, was informed that if she was going to live there she had to see two movies: Breaking Away and Hoosiers. I’ll buy that, in the way that if you are going to live in America you ought to have watched It’s a Wonderful Life. Not that you have to be sold on the message of these movies; there’s a million problems with each of them. (Someday I will write my magnum opus, “Living in Pottersville, Dreaming of Bedford Falls.”) But they’re important markers of the mythologies of those places, the combination of truths and lies we tell ourselves, or that Indianans tell themselves. The things we want to believe about ourselves.

In the case of Hoosiers, that mythology is essentially Small-Town Values, which involves some combination of: Basketball, Christianity, Hard Work Builds Character, Error and Redemption, The Three R’s, Boy Meets Girl (or, you know, middle-aged man meets girl), and David Meets Goliath. I have probably left out a few.

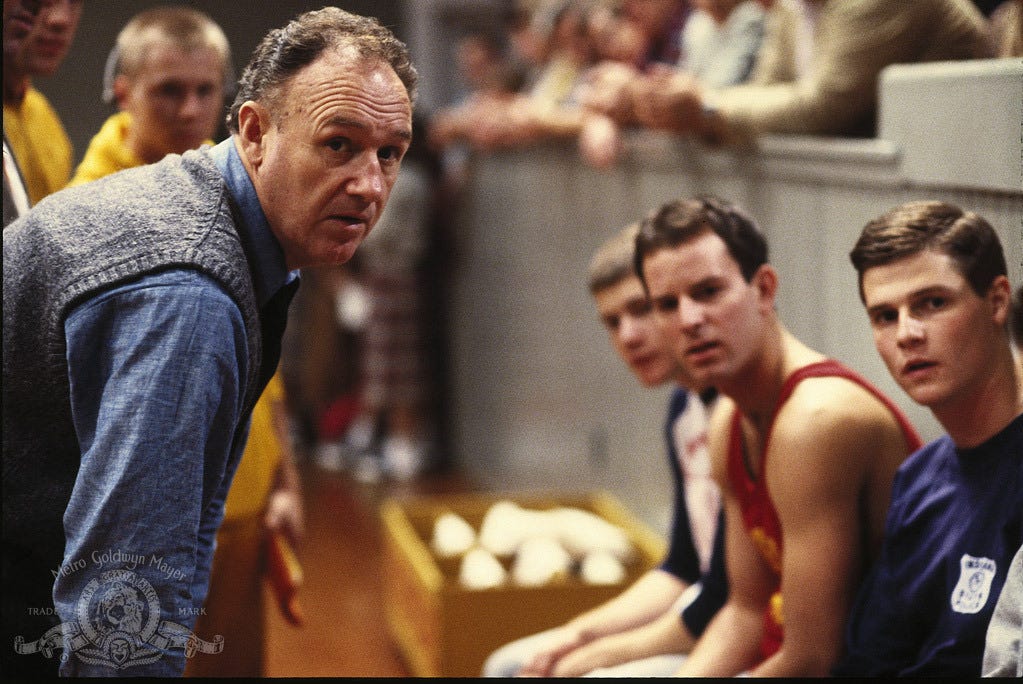

Backing up a minute: Hoosiers is based, loosely, on the Cinderella story of a high-school basketball team from Milan, Indiana, population 1,140. The movie is set in 1951 in a tiny town called Hickory, where a mysterious stranger named Norman Dale, played by Hackman, has been asked to take over coaching the basketball team. He is viewed with suspicion by everyone except the principal who hired him. Some dark event in Coach Dale’s past is hinted at; he thanks the principal for giving him a second chance.

The suspicion surrounding Coach Dale mostly seems to involve him being an outsider but also attaches to his unorthodox coaching ways, which involve fundamentals and running a lot. There’s more to basketball than shooting, he tells the team. One of the players quits in the face of the coach’s demanding approach, leaving Hickory with a total of six players, including Ollie, who stands about 5’4” and is only on the team to enable them to scrimmage each other - which Coach Dale does not believe in.

The father of another of the players, a man called Shooter, was once a basketball hero in Hickory. Played by Dennis Hopper, Shooter is basically the guy described in Springsteen’s song “Glory Days,” but worse, he’s a drunk who his son is ashamed of.

Things happen. Coach Dale wins over the team; moreover, he wins over his doubtful teaching colleague Miss Myra Fleener. (Of all the small-town stereotypes in Hoosiers, the townspeople’s names might be the worst: Rollin Butcher, Doc Buggins, Preacher Purl, and, yes, Cletus Summers.) Coach Dale makes Shooter his assistant coach on the condition that he dry himself out and stop embarrassing his son. Eventually, the Hickory Huskers, out-sized and out-manned but big in heart, roll through Indiana’s state tournament to the championship game against the South Bend Bears. Which I will not spoil for you.

The beauty of mythologies is the way they end up telling us more about societies than those values the society would like to highlight. Such as, in the case of Hoosiers - or, for that matter, Hollywood - the centering of men to the near-exclusion of women, except as needed to realize Boy Meets Girl.

And good lord is Hackman’s romance with Barbara Hershey plastered on top of the story like a mustache drawn on a subway ad. Utterly unnecessary, except insofar as without it - as my sister pointed out - there wouldn’t be a woman in the movie at all, unless you count nameless cheerleaders. No member of the basketball team even has a girlfriend, as far as we see. I suppose it counts as avoiding cliché that there’s no scene at the malt shop where the players grouse about their new coach to their cardigan-wearing sweethearts, but it’s a weird absence.

Or, you know, on our way to Small Town Values and the rest of the list, we never encounter a person of color until that championship game against big, bad South Bend. Which is doubtless partly accurate. It seems possible that a kid growing up in a place like Milan, Indiana, in the 1950s might never have seen a person of color. Nevertheless, a reporter in Hoosiers makes a point of how enormous South Bend’s players are. The pregame prayer before the championship game actually includes a reading of David and Goliath from the bible, South Bend being the Philistines. The movie chooses to do nothing to humanize the opposition - we learn far more about the archrival Terhune team than South Bend. In fact, we don’t even see the South Bend players or their coach before the movie cuts to basketball action, a shot of the arm and body of a Black player going in for a layup, a shot that doesn’t show us his face. (Hoosiers also elides the fact that the real Milan team faced several high schools with Black players on the way to its championship game, including Indianapolis’s segregated Crispus Attucks High School, whose team featured Oscar Robertson.)

Well, Hollywood and storytelling. But at this moment, I’m not inclined to forgive the sort of sentimentality that overlooks certain realities. It’s a problem if your chosen mythology excludes women except as trophies for men to win, and it’s a problem if that mythology excludes Black people except as obstacles to surmount in one’s quest for literal trophies.

Hoosiers obviously got renewed attention, and ended up in my DVD player last weekend, because of Gene Hackman’s recent death. It was fashionable, in the obituaries, to talk about how Hackman never mailed it in; even in “paycheck” roles he gave his all. I don’t recall if Hoosiers was among the examples cited (the way The Poseidon Adventure unfairly was). That may have been because Coach Norman Dale was not that much of a role. Hackman had some back-story to mine - that dark past, alluded to in Scene 1 with the most heavy foreshadowing you’ll ever hope to see - but the script doesn’t offer him a lot to do but pace the sidelines, bark like a drill sergeant, and ask Myra Fleener what she has against him.

Especially, Hoosiers is missing the moment or moments when Coach Dale wins the players over to his side. Which is a problem, because this is the whole story. As the engine of the little town that could, Dale says “I think I can” all the way through, but we kind of need to see what Midwestern Jedi mind-trick he uses to convince the Huskers to go along.

I will pause to note that we do, in fact, see the mind-trick he uses on Hickory’s current basketball star, Jimmy, who holds out from playing for … reasons. Perhaps he doesn’t want to end up like Shooter, endlessly reliving his last shot over beers bought by the friends he once thrilled. In any case, Hackman’s Coach Dale has a deft touch dealing with Jimmy, recognizing that neither scolding nor begging is the route to the boy’s heart.

But with the rest of the team, not so much. One minute they’re complaining about not being allowed to shoot and scrimmage, and Dale is on the verge of being run out of town on a rail. The next minute the whole team and the whole town are on board. The only real difference is Jimmy, who saves Dale’s job and the season by rejoining the Huskers and sinking basket after basket. As sports folks often say, winning creates chemistry. But Hoosiers can’t make too much of that without giving the lie to one aspect of its mythology. Hard work may build character, but stars win basketball championships.

The script is not Hackman’s fault, however, and I will give him points for, indeed, being a professional in what was neither Oscar-bait nor a paycheck role. (At least it wasn’t initially - I imagine the residuals were pretty solid). The temptation, when faced with playing a character lacking in motivation or real depth (yes, yes, that dark secret) or much in the way of signature scenes or, for that matter, poetry - good lord, those locker-room speeches are trite - the temptation is strong for an actor to turn the dial to eleven. A lesser actor than Hackman might have begun chewing the bleachers, hardwood, the nets and backboards to try to fill out the role. Hackman does some yelling, but it will ring true for anyone who has seen a coach on the sidelines during March Madness. And, for that, he mostly saves his yelling for the referees; to his players, during games, he speaks in quieter, calmer tones, a coach who understands the limits to what he can ask of the players in front of him. I will certainly not say Norman Dale is among my favorite Hackman performances, but it does him no discredit.

None of the film’s flaws really matter, though. As a sports movie, maybe it is not worse than Pride of the Yankees or Field of Dreams or most others of the genre that have grown to an outsize place in the zeitgeist. It is no Rocky, however much people who like sports movies apparently want to put it there, but in the end, it does what it came to do, faults and all.

There is, however, one more point about Hoosiers’ mythology that demands consideration. The scene in the film that I can’t shake, that had me waking up two days later and realizing I had to write about Hoosiers, slips by in a moment. I had to watch it twice, and then watch it again later. I am guessing, if you have seen Hoosiers, that you don’t even remember it, or at least didn’t think anything of it.

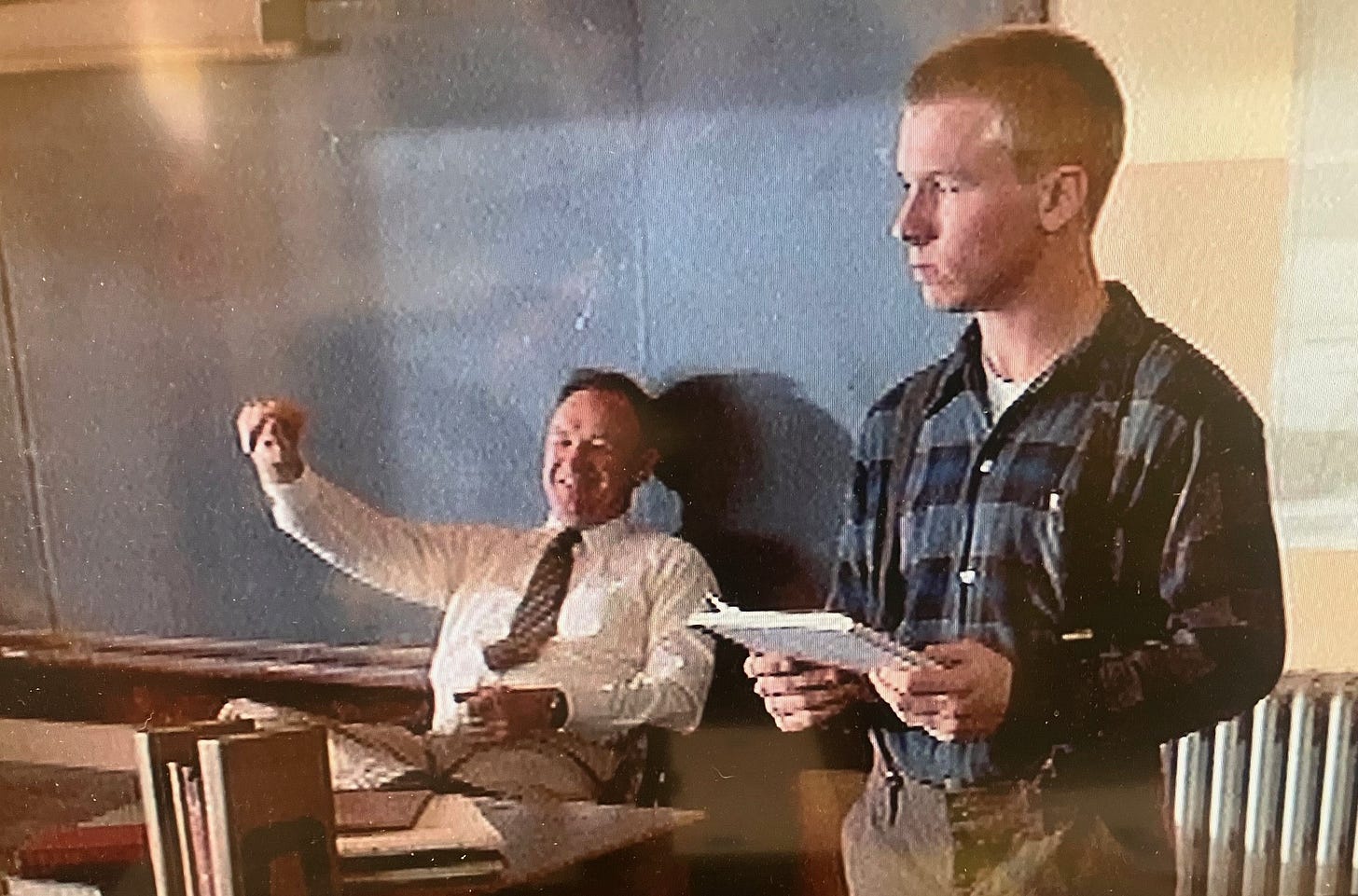

The scene takes place in Norman Dale’s social studies classroom, almost the only time we see him teaching. It’s basically a long establishing shot, showing Dale in the school just before Miss Fleener, now acting principal in place of the man who hired Dale, informs him that the townspeople are about to vote to fire him. (Miss Fleener would be a more impressive figure, and a worthier mate, if she made some effort to stand up to the horde that arrives with pitchforks and torches, but that’s a different movie.)

Just before Fleener gives Dale the news, however, we see a moment of the coach’s class. Ollie, the 5’4” scrimmage-only kid, is reading with halting speech an essay he has written:

Progress. Progress is electricity. School consolidation. Church remodeling. Second farm tractors. Second farm cars. Hay balers. Corn pickers. Grain combines. Field choppers. And indoor plumbing.

Indoor plumbing gets a laugh from the class and a smile from teacher Dale. The bell rings, the students file out. Fleener catches Dale on his way to the gym. As I said, an extended establishing shot. Except, everything is a choice. That scene could have started with the bell and the students filing out; we didn’t need twenty seconds of Ollie stumbling through his essay - and yet, director David Anspaugh gave it to us.

One thing it shows us, quite economically in filmmaking terms, is the kind of education being offered to Dale’s players and their classmates. The first time she meets him, Fleener asks with a smirk whether he’s ever taught before - I presume she has seen her share of coaches masquerading as social studies teachers. As most of us have. At that point in the movie, I thought it was meant to show how she was underestimating him.

But as it turns out, perhaps her cynicism is justified? I mean, come on, that’s not much of an essay. Maybe Ollie is just 5’4” as as student as well as a basketball player, but is the problem instead that Teacher Dale is mailing it in, in a way Coach Dale wouldn’t tolerate on the basketball court? He’s not exactly tearing it up in that lesson, discussing ownership of the means of production, or whatever Indiana’s social studies curriculum may have been at the time.

Or is the problem actually that in Hickory, Indiana, in 1951, an essay consisting of nothing more than a list of examples was as good as might be expected of, or needed by, a high-school graduate?

Which gets at why I think Ollie reading his essay is the most interesting moment in the film - that twenty seconds of throwaway footage before Miss Fleener drops her bomb. Hoosiers unquestionably trades in nostalgia, an image of a moment in time since wiped away - on the verge of being wiped away. In those post-war United States, automobiles - second farm cars - and mechanized farm practices are about to upend rural life and eliminate the kinds of labor that these kids are awaiting, that their fathers will be the last generation to do in the old way. And not just their work (and the jobs in South Bend, too), but the economic viability of a hundred-acre farm with herds numbering in the dozens, and along with it, the economic viability of a town like Hickory or its real-life equivalent Milan.

And especially, the world of Hoosiers is about to be wiped away by that phrase school consolidation. The Indiana School Reorganization Act of 1959 reduced the number of school districts from 966 to 402; the number of districts with fewer than 1,000 students dropped from 801 to 156. In 2025, Milan, Indiana still has a high school, but presumably merged with some other town’s school - its enrollment is now more than twice what it was in the days of Hoosiers. Elsewhere in Ripley County, four other high schools merged to become South Ripley, and Holton, Cross Plains, and New Marion lost their schools. And along with them, their basketball teams, of course.

The baseball writer Bill James, a Kansan of many opinions, once declared that school consolidation had done more to cause the decline of Kansas’s small towns than any other economic force. I don’t know whether that’s true, and if it is true it’s not all bad. I’m inclined to think that South Ripley High School, or even the larger Milan High School, offer far more opportunities to a kid like Ollie than Hickory High ever would have.

And yet, most of those opportunities surely lie somewhere well out of town.

Hoosiers exists not only at the last time a Hickory High made a run at the Indiana high school basketball championship, but the last possible time a Hickory High could have done so. The film doesn’t dwell on that; we get no epilogue, not even whether Coach Dale sticks around to marry his new high school crush. I wish it had done so, if only because in leaving us without the further truths, the film risks becoming - has become, I think - an artifact of toxic nostalgia, the celluloid version of Shooter repeating over and over again the story of that time he took the last shot. As I said above, in 2025 I don’t have a lot of room for sentimentality that ignores all the conditions needed for some number of us to feel those sentiments.

But it’s poor criticism to judge a movie for not being some other movie. At least we have Ollie, in all his naïveté, allowing us to glimpse the future that awaits around the corner.

We watched Hoosiers for the first time the other night, too. It was exactly as you describe. Superficial and glossy. However I kind of liked it, maybe because I’m full of rage and confusion over what our country is turning into. So I took it in as a break from America the Brutal. And in my head, as a woman, I hear Linda Ronstadt singing “When Will I Be Loved” and a little voice asking When will I be seen?

You’re an elegant writer Chris. Thank you for this. Now I’ll think more deeply about that shallow movie 😂